Basic HTML Version

41

In the same text, one finds the rationality of Samyn’s

designs compared with those of the so-called revolu-

tionary architecture imagined by Claude Nicolas Ledoux

and Étienne-Louis Boullée from the late eighteenth

century, which was standardised somewhat by Jean

Nicolas Louis Durand. Such a comparison, like the

previous one, places the work of Philippe Samyn in

one of the essential traditions of architectural history,

which evolved concurrently (or alternately) with the

so-called organic or accumulative tradition, which

includes a part of medieval architecture. Does all of

this add up to an aesthetic? Yes and no, although there

is indisputably such a thing as a Samyn style, and a

unique approach to the problems of architecture, urban

planning and landscape. To quote him once again, we

see that, ‘it is not a question of posing as some sort of

technological genius: we are probably heading towards

a co-existence of various types of building. Alongside

new, hi-tech buildings and organic structures, the

maintenance and upkeep of traditional buildings, both

old and new, will continue until a good part of this

legacy disappears.’ This is no doubt a good definition

of the roadmap for today’s architects, especially if they

are interested in avoiding waste. In parallel to this, one

should note Philippe Samyn’s love for certain ancient

architectural forms, including those of classical archi-

tecture from all parts of the world, indeed, any place in

which reason and balance can be found.

The aesthetic project of Philippe Samyn is certainly

not limited to ‘Beauty is Utility’, one of functionalism’s

great slogans, but he has clearly adopted the idea

of not loading down a construction with decorative

elements that are symbolic or allegedly inspired by

industrial design, the inclusion of which blurs our

ability to read the architecture. The fascination with

geometry led him to the study of fractals, as well as

to the design of the theoretical Wing building project

in 1970

(01-000)

and to the spherical shapes in the

project for the Musical Instrument and Crafts Museum

in Dranouter

(01-254; unbuilt)

.

When it comes to including works of art, Philippe

Samyn does not turn them away, but he accords

them only a modest place. At the Houten fire station

(01-373)

, children from the small town decorated

the standard-sized sheets that clad the large verti-

cal wall dividing the space. For the Espace Christian

Dotremont in Nivelles-Nord

(01-379)

, Samyn asked the

musician Henri Pousseur to fill the space with a sort

of electronic carillon, and also invited the artist Yves

Zurstrassen to make a contribution. A large fresco by

Kris Van de Giessen adorns the ceiling of the restaurant

at Orival

(01-365)

; in Hellebecq

(01-386)

, the panels

are decorated with large reproductions of the finest

works of art from the Museum of Fine Arts in nearby

Tournai. At Rixensart

(01-410)

, Leon Wuidar, a con-

structivist painter from Liège, contributed to the design

of the floor lighting in the foyer of the auditorium for

GlaxoSmithKline.

Further examples are given in the anthology. Generally

speaking, as he stated in an interview in 2006, Philippe

Samyn encourages each artist in his or her specialisa-

tion: the painter must paint, the sculptor must sculpt,

and so on. A concern for contour modulation is clearly

not lacking in the work of Philippe Samyn, but he is

interested in the neatness and clarity of links, assem-

blies and juxtapositions of materials: new elements with

each other, and new elements with pre-existing ones.

For Philippe Samyn, architecture, although it is often

synonymous with rigour, is not synonymous with dry-

ness. The ‘sensual’ aspect is essential, and it can be

found in his use of materials, colours, light and even

acoustics. This preoccupation has led him to several

interesting creations, including a ‘pure’ grey tone

that acts as a veritable colour mirror, a ‘raw’ linoleum

(unfortunately a material little used today) and various

other fabrics. He appears to think that the architect

has been thrust into the role of a buyer of materials

and technical processes by the current state of much

of the construction industry and the regulations of

public procurement. Everyday life is a constant struggle

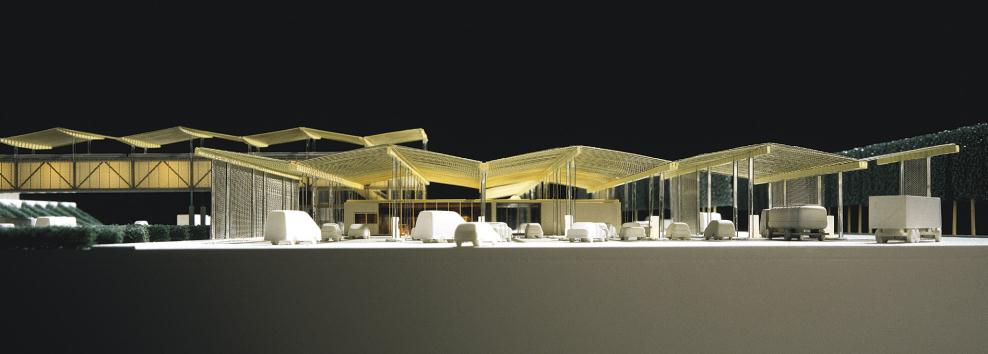

01-386

First project for the Totalfina

service station, Hellebecq,

1999–2000