Basic HTML Version

40

architecture and urban planning, and what would be

the reflexes to overcome, even those associated with

what we still call modernism. In short, if all goes well,

entering one’s century is a matter of constant question-

ing. When Philippe Samyn wonders, in Pierre Loze’s

book, how to ‘become modern’, there are grounds for

wondering what meaning the adjective ‘modern’ still

holds today.

15

The theme of the book is contained in

its subtitle: Entretien sur l’art de construire (Discussion

about the Art of Building). One of the central ideas of

these interviews seems to be the need to match the

technical and economic content of architecture with its

image: ‘The initial works of the modernist movement

were still made via craftsmanship. Behind the white

coat of plaster there was craftsmanship. The forms

looked ahead to liberation with respect to the material

that was not yet technically possible. […] Today, we are

at a unique moment in history, where construction proc-

esses have become truly modern, completely industri-

alised and capable of implementing new materials. The

dream of an architecture that uses the least material

possible – an architecture not weighed down by matter,

by classical plasticity – is finally coming true.’

Later, Philippe Samyn writes, ‘At the start, the modern-

ist movement was much less modern than it is now,

both because it did not have the means to match its

ambitions, and because it was subjected to a century

and a half of decorative art and distractions.’ This is

a statement that Adolf Loos would perhaps not have

challenged, especially since there is still much admira-

tion for his famous article from 1910, ‘Ornement et

Crime’,

16

as well as for his historicising Viennese

adaptations. He is also admired for his provocative

entry in the 1922 Chicago Tribune competition, which

took the form of a single colossal Doric column, about

which he said, prophetically, ‘If I don’t built it, others

will’. One cannot avoid comparing Philippe Samyn’s

remarks to the mechanistic or futurist dreams that

marked the beginnings of modernism or, in a different

way, to the famous little house (since disfigured) built

in 1928 in Auderghem by Louis Herman De Koninck.

The house, through the use of facades made from

reinforced concrete beams/sheets instead of mortar

and stone blocks, brought together the aesthetic and

the technical aspects of an avant-garde that was still

unacquainted with the physics of building. The dream

of a partially dematerialised architecture can also be

seen in the work of Victor Horta, who at one point justi-

fied the metallic structure of the Tassel house through

its small footprint – the same technique used by

department stores, whose upper storeys seem to float

above a ground floor made almost entirely of glass; a

dematerialisation that has nothing to do with baroque

and rococo tastes for optical illusion.

We should point out that the technical project

expressed here by Philippe Samyn is part of one of

the great moral themes of modernism, that of the

use of materials depending on their ‘vocation’ and

performance.

17

Nevertheless, the public’s visual habits

are such that they were sometimes dismayed by the

flimsy appearance of Philippe Samyn’s framing. This is

doubtless the case with the two cylindrical buildings

discussed in Chapter 3 (the social services building

in Marolles

(01-413)

and the Eversite office build-

ing

(01-368)

).

18

Philippe Samyn’s research into wind

turbines and volume indicators is also in line with this

‘moral’ perspective.

Comparisons can also be risky. Nevertheless, Koen

Van Synghel’s very cautious introduction to Samyn &

Partners, Architects and Engineers

19

draws interest-

ing parallels with Norman Foster: ‘The architecture of

Samyn & Partners is ostensibly led by the principle of

reason. Order, a geometrical layout, complete calcula-

tion of the physics of the minimal use of materials

and their durability – all of this adds up to a sane

economic and ecological approach to construction. In

this respect, Samyn has the same approach as Norman

Foster, who upholds the idea that, since antiquity,

architecture has been, by definition, the object of con-

struction technology.

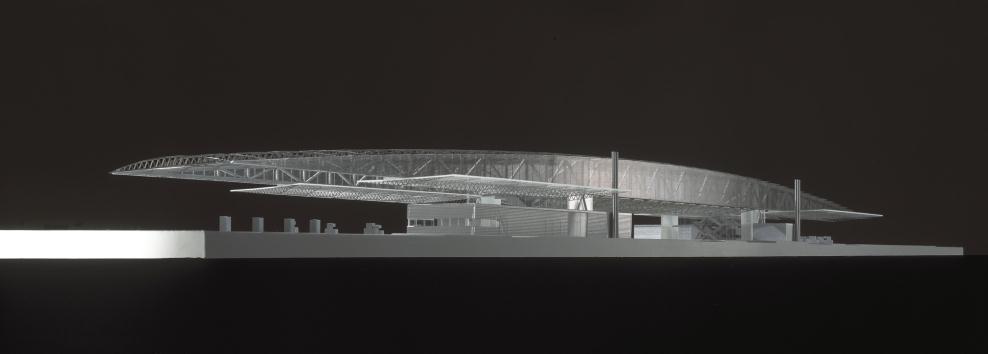

01-365

Orival service station

and bridge restaurant,

1998–1999