Basic HTML Version

37

demolition companies are not short of work. During

his studies at

mit

in 1971, the young Philippe Samyn

began to become aware of the problem. Soon this

concern was ever-present, both in his personal crea-

tions and his theoretical writings. As he has shown in

several transformational projects, it is often possible

to take advantage of an existing structure, such as his

recent work on the Spaarlaken building

(01-465)

or the

Erasmushogeschool in Brussels

(01-407)

, managing to

get them to comply with the strictest safety criteria. In

this respect, it is doubtless the most ordinary buildings

that are the easiest to adapt. And yet the point is not

to criticise inventors, whether of reinforced concrete or

plastics. It is others, less scrupulous no doubt, who do

not think twice about taking the most immediately

profitable path when building structures that end up

being hazardous. It should be emphasised again that,

with few exceptions, the training given to architects

and engineers does not yet address this issue. The

fact remains that the very production of certain con-

struction materials needs to be re-examined, and that

regulations (independent of regional differences cited

above) are far from being coherent; the same is true of

environmental incentives.

It is worth mentioning two examples of regional dif-

ferences here. The Haute Qualité Environnementale

standard (Environmental High Quality, or

hqe

) – which

Philippe Samyn used for his project for the Tour Signal

at La Défense in Paris

(01-533)

– was first ‘a consensual

theoretical foundation before becoming a trademark (!)

in France. The aim of

hqe

was to integrate principles

of sustainable development, as defined at the Rio

Summit in 1992, into the built environment.’ It is clear

that there is a large-scale effect and that the question

of ‘overall cost’ of construction and urban development

is an important evaluation criterion. The concept of

sustainable construction, which has been implemented

in Philippe Samyn’s projects and structures in Belgium,

rests on three fundamental pillars as defined by the

Seco control office and the Scientific and Technical

Construction Centre: the ecological dimension, the

social dimension and the economic dimension. The

ecological dimension also includes climate variations,

biodiversity and the provenance and use of materials.

The social dimension is concerned with the wellbeing

of users, building accessibility and even aesthetics

(although one wonders what criteria are used to judge).

The economic dimension covers the analysis of the

functions of use and risk analysis, the value of the ‘life

cycle’ and problems of upkeep. Culturally speaking,

Philippe Samyn aptly points out that there is a contradic-

tion between the culture of architects (who are, at best,

concerned with the social aspects of their work) and

that of engineers, which is based on criteria to do with

the physics of the construction. It is up to both sides to

bridge this gap through training and education.

1

Philippe Samyn, Etude de la morphologie des structures à l’aide

des indicateurs de volume et de déplacement, Brussels, Royal Academy

of Belgium, 2004.

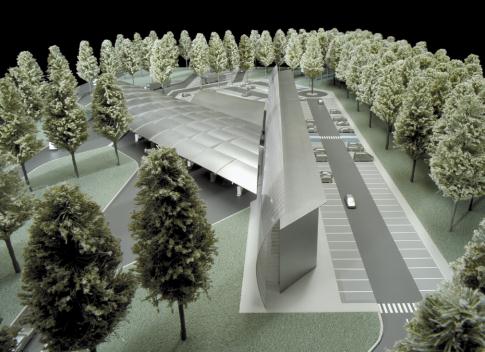

01-515

Total service station,

Ruisbroek, 2007

01-407

Erasmushogeschool,

Brussels, 2000–2002